Article by Stefano Macchia

If most cities in the world could be easily described and portrayed with a map, seldom do some resemble a compass with many needles. There the imperial lives along the playful, the ritual stands proud next to the profane; but the wind in Beijing still blows frequently, yet carefully, as if aware of the fragility held by the secular walls of the city’s Hutongs. Beijing moves fast and moves forward, endorsing a centrifugal urban development which keeps tight the memory of a centripetal past, when the streets of a gone but not forgotten empire converged at the Forbidden City, heart of the metropolis.

Here the red bricks and the gold columns whisper the secrets of emperors, concubines and soldiers who shaped the history of China. It is difficult, if not impossible, to visit all the 9999 rooms found in the palace: nonetheless the grandeur of this site can be breathed up even in the majestic gardens outdoors. Completed in 1420, it hosted 23 emperors from Ming and Qing dynasty, whose legacy is now witnessed by the incredible treasuries and objects now displayed in the main buildings of the museum. But if walking through the threshold of the Forbidden City could be an overwhelming step for most tourists, a valid alternative to admire its grandiosity is from the Jingshan hill, artificially raised with the earth dredged from the palace moats. From up here the old imperial axis is a ruler laid across the city: the yellow tiles glow like embers at dusk, the courtyards align in perfect geometry and beyond the walls the modern capital hums, impatient, around its rings.

Step south and the air widens into Tian’anmen Square. The Gate of Heavenly Peace frames the north; to the west the Great Hall of the People, to the east the National Museum; at the center the Monument to the People’s Heroes stands like a metronome for ceremonies and seasons in its solemnity, sometimes severity.

Beijing proudly wears its contradictions and its paradoxes, even when it comes to the weather. A freezing winter coats the city from November to March, when it slowly leaves space to a ridiculously warm summer. When the heat of August makes it unbearable to wander through the narrow streets of Beijing, take refuge by water at the Summer Palace, just as the emperors used to do during the warmest days in the capital. This huge oasis nestled in the north-west of the city provides an enchanting mix of botanical gardens with several buildings asserting the quality and determination of old Chinese handcraft.

Exploring the Chinese capital means allowing all senses to be fondled: different kinds of smells and sounds can be met within the six rings of the city. Incense thickens the air at the Lama Temple. Saffron robes move like small flames among red pillars and prayer wheels click in a steady rhythm. Here the city’s speed bows briefly to ritual.

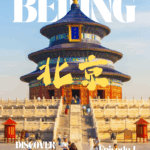

South of the core, the Temple of Heaven sits inside a park of old cypresses, a quiet geometry for aligning earth and sky. The circular hall rises on three white terraces; blue-glazed tiles catch the light, red doors repeat along the axis, and stone balustrades pull you forward. Mornings bring tai chi lines and kites.

The hutongs are the city’s small print: narrow lanes that explain what the boulevards only promise. Grey brick walls hide courtyards where persimmons dry, bicycles lean and pomegranate trees mark the seasons. Thresholds are shallow, yet meaningful: stone drums, heavy doors, a red couplet curling at the edges. In the mornings you hear radios, broom bristles, the clack of mahjong; by late afternoon, electric scooters thread past vegetable sellers and repair carts. Light arrives obliquely, strips of sun sliding along walls and into doorways. Some alleys have been polished into cafés and boutiques; others remain strictly domestic, practical, unadorned. Both are authentic in different ways: one performs hospitality, the other privacy. Walk slowly, greet neighbors, keep your camera low. Notice the public taps, the coal boxes now repurposed, the rooftop cables knitted overhead. The lanes are routes but also rooms. Here, finally the map shrinks. The city feels near. It is easy to uunderstand why people still choose to live here, even now.

Even the night draws a darker ink line around Beijing. On the shores around the lakes of Shichahai rickshaws trace quick commas along the streets. In summer, paddle boats drift like punctuation, whereas in winter skates score the black glass of ice. It is nightlife with a courtyard heartbeat, encompassing rowdy and tender at once.

For those who come seeking modernity, head east to the business district: glass and steel lifted over broad avenues, silhouettes sliced by the ring roads. A bottle-shaped tower rises above; a looped building frames the sky. Skybridges link blocks, accompanied by LED facades pulses which camouflage with the electric taxis queues. On clear days the mountains draw a faint line; on hazy nights, towers seem to float. The city also moves vertically, at a counterpoint to the hutongs within the same city, but another tempo.

When it comes to the table, impossible not to mention the Peking duck with its practical, precise rituals: crisp skin carved at the table, thin pancakes, sweet–savory sauce, scallion and cucumber batons. You assemble each bite by hand; the flavor is smoky and clean, with a firm contrast between crackling and tender.

Beijing rewards alternation: walk, look up, slow down. The city keeps its axis yet changes pace; memory and momentum share the same streets. What feels monumental at noon becomes intimate at dusk and what seems remote from Jingshan feels close again in a hutong doorway. Here modernity and memory are not rivals but neighbors, sharing walls and stories. Leaving Beijing makes you feel warmth and curious to return.

0 Comments